Thursday: I wake early, shower promptly, don a collared shirt, leave The Kid a note, head for an appointment. Aside from the waking early part, in three months of CoronaWorld I’ve done none of those things. (Well, one collared shirt, for a videoconference job interview.)

My appointment is in the Brooklyn office of the U.S. Census Bureau. Three months ago I passed a telephone job interview, amusing in its robotic simplicity. The interviewer read questions from a screen, asked no follow-ups, discouraged me from straying beyond each question’s four corners, wanted to know nothing about me beyond whether I was likely to do a competent job knocking on people’s doors, asking about their lives, filling out forms. He hired me over the phone for the position of Enumerator; I was awaiting notification to get fingerprinted when CoronaWorld arrived, shut down the hiring process.

On Tuesday I got an email: some Census Bureau offices across the nation are accepting fingerprinting appointments. I logged into my applicant account, clicked a few links, found that an office on Myrtle Avenue, a couple of miles from my apartment, had appointments this week. I scheduled one for Thursday at 9:30 a.m.

The email says the Bureau will require two forms of I.D. The form lists more than a page of alternatives, acceptable (social security card, military I.D., birth certificate copy with official seal, voter registration card, certificate of naturalization or citizenship, Native American tribal I.D., PIV card — whatever that is) or not (school or work I.D. badges, a dozen other things). I’ve got a passport and a driver’s license, so I’m set.

In CoronaWorld applicants are asked to:

- Wear a facemask throughout your visit unless your photograph is being captured

- Thoroughly wash with soap and water and dry your hands completely

- Avoid shaking hands or touching others after you wash your hands

- Wait in your car, or outside the building, until your appointment time

- Inform the fingerprint operator when you are ready for your appointment

- Practice social distancing by staying 6 feet away from others

- Thoroughly wash and dry your hands after your appointment

I ride my bike (east on Willoughby, north on Lewis) to Myrtle Avenue, the Brooklyn Census Bureau office. There’s no place to lock my bike. The office is beneath M train tracks, formerly the Myrtle Avenue Limited — the last stretch of Brooklyn’s elevated railroads. (Until the 1940s it ran over the Brooklyn Bridge; until the 1960s it ran to downtown Brooklyn; now the above-ground section only bends northeast through Bushwick to Middle Village, Queens.) I have only a U-lock, no cable; I can’t connect to the track’s pillars. I walk to the Sumner Houses on the corner of Lewis and Myrtle, lock to the public housing unit’s low border fence. This is illegal, I’m sure, but I’m hoping I’ll be out in under an hour.

Gentrification waves have yet to reach this northwest corner of Bushwick, where the main businesses are auto body shops, fast food outlets, Dollar Generals. Everyone I see, save two elderly south Asian women walking to the Food Bazaar, is African American. That includes two 20-something gentlemen in line, each standing near a piece of electric tape slapped on the sidewalk 6 feet apart. I step into the office, an unadorned concrete cube with a door sign informing us that the Social Security Office has moved. A security guard looks up, says, “Fingerprinting?”, tells me to wait outside, stay 6 feet apart. I walk outside.

My routine for encounters with bureaucracy: shift to "Indonesia mode." For two years in my 20s I lived in Jakarta as the coordinator of a small U.S. volunteer agency that sent about 20 Americans to teach English or work with non-governmental organizations; my job was to shepherd their visas and work permits through a labyrinthine maze of (depending on the job) seven or nine Indonesian federal agencies whose stamps of approval each required. We paid no bribes; I rode my small motorcycle across the filthy city, drank a lot of tea, schmoozed a lot of mid-level bureaucrats who, after two or four or six visits, moved the process to the next office, where I started anew. Frustration was my enemy, friendly patience my ally.

For today, that means I’ve brought a book, am set to wait as long as needed, which turns out to be 20 minutes before the security guard nods me inside. He sits in a hallway adjacent to a small foyer; a glass door leads to a smaller waiting area, separated from the rest of the office by a plasterboard wall, a door with a push-button security lock, and plastic paneling in front of a staff assistant’s desk.

The assistant asks for my two forms of I.D., signs me in, tells me to wait. The guy ahead of me in line sits in the area’s one chair.

“Small space,” I say.

He nods.

It’s hot; I decide to step into the airier foyer. The security guard waves me back inside. I can’t stay 6 feet from everyone in there, I say. You have to wait inside, he says. Okay, I say. I step inside.

“So much for that idea,” I say.

My predecessor in line nods.

I sit on the floor, break out my book.

Two men emerge from the hallway behind the security guard — another government agency’s space, I assume. One man says the second man wants to use the Census Bureau’s bathroom; I don’t catch it all, but apparently the first bathroom he tried to use is a disgusting mess. The assistant buzzes the second man in; seconds later he is escorted out by the only white person I see all morning, a 50-something man, walrus mustache, walrus physique, who says sternly that the bathroom cannot be used by non-employees. The unsatisfied bathroom user looks upset. The assistant apologizes. The man steps out to complain to the security guard, to no avail; he and his minder disappear back down the hall.

A woman in her 50s signs in at the same time my predecessor in line is called inside. She takes the chair; I stay on the carpet. I’m almost done with my chapter when my predecessor walks out, exits the building without a sideways glance.

“You can go in,” the assistant says. “Use the hand sanitizer to your right. The office is on your left.”

I walk in, catch a quick glimpse of a dozen people spread among at least two dozen desks in a featureless room with a thin blue carpet. I see the walrus guy, who doesn’t look up. I sanitize, step into the small square office, where a Middle Eastern woman with fashionable eyeglass frames asks for the barcode on my job acceptance letter. I put my phone on her desk.

“Not the fingerprint request letter,” she says. “The original acceptance letter.”

I scroll through my email, find the letter, download it, put the phone back. She scans it.

“Okay,” she says. “Put that away. Now your two forms of I.D.”

I put them on the desk. She taps at her keyboard.

“Okay,” she says. “Put those away. Now I’m going to tell you how to get fingerprinted.”

She explains. There’s no ink — my visions of police station booking procedures may be decades out of date — but a scanner the size of a credit-card reader. She wipes the glass panel with a sanitized wipe.

“Your job must have got about four times harder in CoronaWorld,” I say.

“Uh-huh,” she says. “Don’t step forward until I tell you.”

“Uh-huh,” she says. “Don’t step forward until I tell you.”

I step back.

“First you’re going to scan the four fingers of your right hand, then the four fingers of your left hand, then your two thumbs. You press down until all the lights are green. Then we’ll do it again. Got it?”

“Yes.”

“Okay. Step forward.”

It’s tricky to get my finger pads pressing with sufficient pressure at the right angle; it takes a few tries. She says nothing until a light beneath the glass panel blinks, then says, “Left hand,” “Thumbs,” “Right hand,” “Left hand,” “Thumbs.”

“Okay,” she says. “Now your picture. Step back. Take off your mask.”

She makes me realign a chair before a blue screen attached to a thin metal stand with a tripod base like the ones we broke out when it was movie time in grammar school. I sit. She tells me to keep a neutral expression. She takes a long time adjusting a plastic device with the camera lens.

“It’s saying your eyes are closed. You have to open your eyes.”

I open my eyes wide, imagine my photo will look like an axe murderer feigning innocence.

“Okay. Put your mask back on. I’m going to tell you what happens next.”

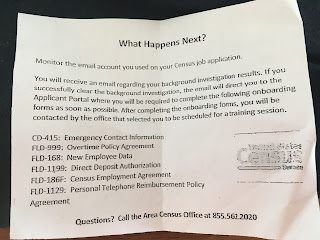

She hands me a slip of paper entitled “What Happens Next?”

She hands me a slip of paper entitled “What Happens Next?”

“When we’ve completed your background investigation you’ll get an email. Don’t be surprised if that takes two or three weeks. There’s no need to call us; you’ll get the email eventually. If you successfully clear the background investigation, the email will direct you to the applicant portal; you’ll need to complete the six forms listed there. Once you’ve done that, we’ll contact you about a training session.”

“Okay,” I say. “Any sense of the timeline of all that?”

“My guess is you won’t get called for training until next month. Maybe August. You’ll probably start work in August. Maybe September.”

“Okay,” I say. “Thanks.”

“Good luck,” she says. Her tone could mean: “Drop dead.” "Sanitize on your way out."

I ride my bike home. An hour later, the Census Bureau sends an email telling me to log into the Applicant Portal to fill out the six forms; if I fail to do so within 48 hours, I'll have to re-enter the hiring pool, start the process over.

Have I passed the background check? Who knows? I fill out the forms, await the next email.

No comments:

Post a Comment